The Workshop Way is a series of white papers, research reports, and reflections that articulate the “why” behind the way we approach our work.

Brian Schermer, Ph.D., AIA, Principal, Workshop Architects

Animating Spirit

The Progressive Architecture of the Michigan Union

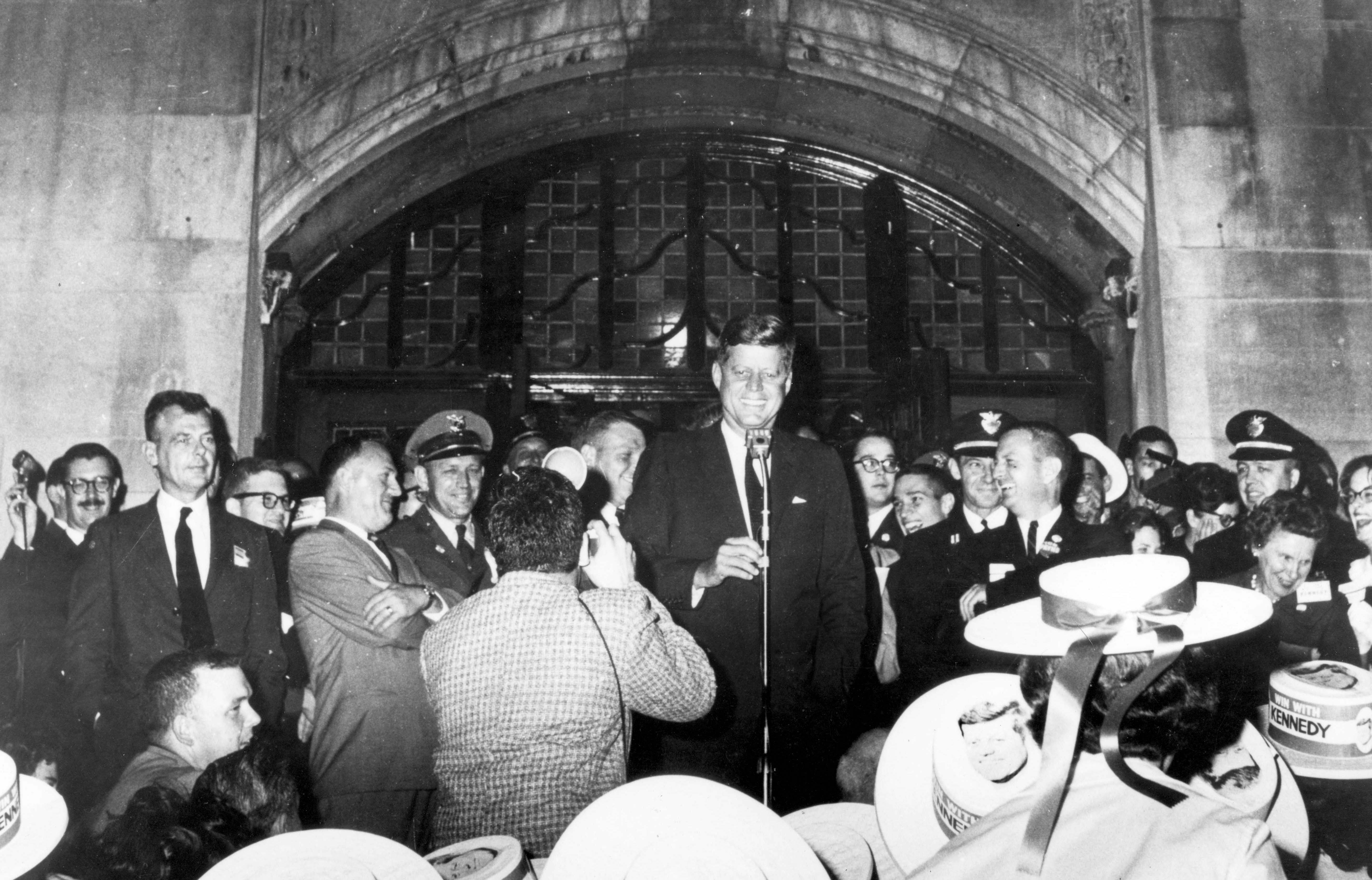

No place at the University of Michigan embodies its sense of campus community more than the Michigan Union. It is a vital social hub, a symbol of Wolverine pride, and an inspiration for new ideas and idealism. This reputation derives from the Michigan Union’s historic role as a backdrop for progressive thought and action. It is the site of President John F. Kennedy’s 1960 speech that inspired the Peace Corps. It is also the home for innovative student support services like the Spectrum Center, (the nation’s first college LGBT support center founded in 1970. As the home for Central Student Government, student organizations, and countless events, the Michigan Union remains an incubator for ideas, initiatives, and progressive thought.

John F. Kennedy on the steps of the UM Union October 14, 1960. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Less recognized but equally important, however, is how the architectural conception of the Michigan Union building exemplifies Progressive Era ideals of social reform and aesthetics. Indeed, its architects, brothers Irving Kane Pond and Allen Bartlit Pond of Chicago, held deep ties with leaders of the Progressive Era, including social reformer Jane Addams. The building embodies the ideals of the Arts and Crafts Movement: artistic integrity, honest structure, and fine workmanship. To the Midwestern reform-minded leaders who founded the Michigan Union, its architecture symbolized social justice and community service.

The Michigan Union stands today as one of the foremost architectural examples of a true campus center. That it is still a cherished icon, despite decades of physical alterations, functional changes, and profound shifts in education and society, is a testimony to the power of its architecture and the ideas behind its creation.

The establishment of the Michigan is part of a larger narrative about the emergence of student unions on college campuses in the United States. Yet this student union (as well as others designed by Pond and Pond for Purdue University, Michigan State, and the University of Kansas, as well as the Michigan League on the Ann Arbor campus) are distinguished by an architectural expression which animates the building and conveys the values of social reform associated with the politics and aesthetics of the Progressive Era.

The Jane Addams Connection

Architects Irving and Allen Pond were born in Ann Arbor, attended the University of Michigan, and established their architecture practice in Chicago. Chicago was an important center for Progressive Era thought and social reform during the last decades of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th. The many progressive-minded Chicagoans represented a wide range of artistic and political endeavors including the visual arts, architecture, labor, literature, politics, law, women’s suffrage, and education. They included leaders whose names are familiar today, such as philosopher and educator John Dewey, who taught at both the University of Michigan and the University of Chicago, and social reformer Jane Addams.

Addams is a key link to the Michigan Union to the Progressive Era. Addams established Hull-House in 1889, an influential and widely emulated “settlement house” or social services organization dedicated to lifting the immigrant masses from poverty, celebrating their cultures and traditions, while also helping them to assimilate into American society.

Born in Illinois in 1860, Jane Addams attended Rockford Female Seminary. That is where she encountered the writing of the English art critic and social thinker, John Ruskin. Judging art through a moral lens, Ruskin believed that art both reflected and influenced the moral character of a society. Ruskin denounced industrial capitalism, which he faulted for assailing the dignity of human labor and inducing systemic poverty, crime and other social ills. He called for an approach to art and architecture that would, through a high level of craft, aesthetic integrity, functionality, and structural honesty, enable workers to reclaim their dignity and thus build a more moral and just society. Ruskin’s writings inspired the Arts and Crafts movement, which, in the words of William Morris, one of Ruskin’s most ardent followers, sought to create art “made by the people for the people as a joy for the maker and user.”

Inspired by the writings by Ruskin and the spirit of social reform, Jane Addams and companion Ellen Gates Starr traveled to England. There, they visited the first university settlement, Toynbee Hall in London, a place for Oxford University students to work with the poor. This visit inspired Addams and Starr to establish a similar settlement in the United States.

Addams scouted potential sites in Chicago. In 1889, she met the socially-minded architect Allen Bartlit Pond who was himself a volunteer at the Armour Mission. Pond helped Addams find the site for Hull-House, thus beginning a long-lasting friendship and association that included his serving as secretary of the Hull-House Association and member of its board for the rest of his life. It was also an important business connection for the firm of Pond & Pond. Of his brother’s friendship with Addams, Irving Pond wrote:

“It was the beginning that changed both of their lives and provided the Pond brothers with one of their most devoted clients and life-long friend. It also provided the brothers with an outlet for their elevated sense of social duty and community service.”

The Hull-House Settlement

Hull-House provided Chicago’s immigrant communities a kindergarten, daycare, clubs for older children, and classes for adults. It included an art gallery, library, art studio, music school, and employment bureau as well as the first public playground, gym and swimming pool. It eventually grew to 13 buildings occupying a half city block. But the influence of Hull-House extended beyond its immediate mission to improve the conditions of the immigrant population. Hull-House was also an incubator of social reform and Progressive causes, which included public sanitation, labor reform, and legal protection for women, the poor and other disadvantaged groups. It attracted a wide range of advocates for women’s suffrage, child labor laws, and such organizations as the Chicago Women’s Trade League, the Chicago chapter of NAACP, the Immigrants Protective League, and the National Conference of Social Work.

Hull-House also became a cultural and intellectual center for public discourse and debate, including Chicago’s Arts and Crafts Society. In Art and Labor, Eileen Boris writes that the Chicago group embraced the arts and crafts style as part of its program of social uplift:

“For the residents of Hull-House and many of the social scientist-reformers of the University of the Chicago Arts and Crafts Society—in conjunction with the reform impulse— stood as the appropriate aesthetic for their new order rather than a means in itself to achieve industrial democracy and social betterment.”

Social reformer and Nobel Peace Prize recipient Jane Addams around 1924 (George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress)

Toynbee Hall in London inspired Addams to create a settlement house in Chicago. The World Today Magazine, April 1902 (Public Domain).

Hull-House borrowed architectural motifs from Toynbee Hall. Hull-House Yearbook Photos (University of Illinois at Chicago)

In her memoir, Twenty Years at Hull-House, Addams glowed about the buildings designed by Pond and Pond:

“These first buildings were very precious to us and it afforded us the greatest pride and pleasure as one building after another was added to the Hull-House group. They clothed in brick and mortar and made visible to the world that which we were trying to do; they stated to Chicago that education and recreation ought to be extended to the immigrants.”

The design for Hull-House included allusions to Toynbee Hall. It also conveyed the kind of straightforward and honest expression associated with the Arts and Crafts style. In the introduction to Irving Pond’s autobiography, historian Guy Szuberla comments about the lack of architectural pretense in the Coffee House at Hull-House:

“In the New Coffee House at Hull-House (1889) they stripped the interior bare to the fireproofing tile and common brick walls, but still brought out form and beauty from these coarsely utilitarian materials. Such tile and brick surfaces were ordinarily covered with plaster or otherwise disguised. Their honesty in handling these materials led House Beautiful—then a champion of Frank Lloyd Wright and other Prairie School architects—to find functionalist virtue in their design: ‘the room is structurally what it seems to be and for the most part all (the) charm of color and texture proceeds directly from the actual structural materials.’”

Both the social mission of the Hull-House settlement and the arts and crafts ideals associated with it rippled throughout the reform-minded institutions in Chicago. Their close connection to Jane Addams led Pond and Pond to similar commissions. In 1884, social reformer Reverend Graham Taylor commissioned the firm to design the Chicago Commons, which combined elements of church and settlement house. Commissions followed for the Northwestern University Settlement, the Ethical Society’s settlement, Henry Booth House, and Gads Hill Settlement. The architects earned a reputation as the grandfathers of the settlement house movement in Chicago.

In his autobiography, Irving Pond wrote that it was because of the broad experience they had gained “in the “housing and accommodation of various classes of people in these settlement house problems” that University of Michigan professor, and later law school dean, Henry Moore Bates sought out Pond & Pond for the design of the Michigan Union. Bates had been a member, along with Irving Pond, of the Chicago Literary Club. According to Pond, Bates was “a constant factor in the uplift” movements in Chicago before moving to Ann Arbor. In his introduction to Irving Pond’s autobiography, Szuberla makes clear the parallel aims of the Michigan Union and Hull-House:

“In short, the Ponds and Bates conceived of the student union much as Jane Addams…thought of the settlement house—as a social center built to ameliorate class conflicts and shape a new and unified community.”

Founding of the Michigan Union

Henry Moore Bates played a key role in the founding of the Michigan Union. He left his career in Chicago in 1903 to teach at the University of Michigan Law School and served as dean from 1910 to 1939. Writing in The Michigan Alumnus in 1905, Bates reported that the earliest discussions about a clubhouse for a union at Michigan began in 1898. According to Bates, the idea gained momentum the year of his arrival when the Michigan Daily printed an interview with President James Burrill Angell which expressed support for a union. In 1903, Michigamua, a senior society, called a meeting and established a committee for its formation. They held a dinner on November 11, 1903, to which over 1,100 people attended.

Appraisal of Bates’s record of events reveals that student union was to have at its core both an educational and a social mission. The Union was “to promote university spirit, to increase social intercourse and acquaintance with each other’s work among the members of the different departments and other University organizations.”

Later in the Alumnus article, Bates asserts the centrality of the communal role envisioned for the union: “It will be the center, an inspiring center, of all University and social life, in the broad and better sense of the term social.”

An emerging theory at that time was that a complete education must encompass more than the student’s experience of “boarding houses, recitation rooms, and libraries,” but must also include the social component that was characteristic of English formal education. Indeed, in his article, Bates quotes Woodrow Wilson, who was then the President of Princeton University and influential progressive voice, on the topic:

“…After all, perhaps, the greatest part of education, mental and moral, is derived from that attrition of mind upon mind which takes place in the companionship of student with student, after recitations are finished.”

Bates’s writing thus reflects the progressive impulse to improve the social and intellectual life of a university through a strong sense of community. In addition to this high-mindedness, Bates also expressed concern about keeping the all-male student body productively engaged lest they surrender to less lofty temptations: “The Michigan man when not at work or eating is practically forced onto the street or to worse places.”

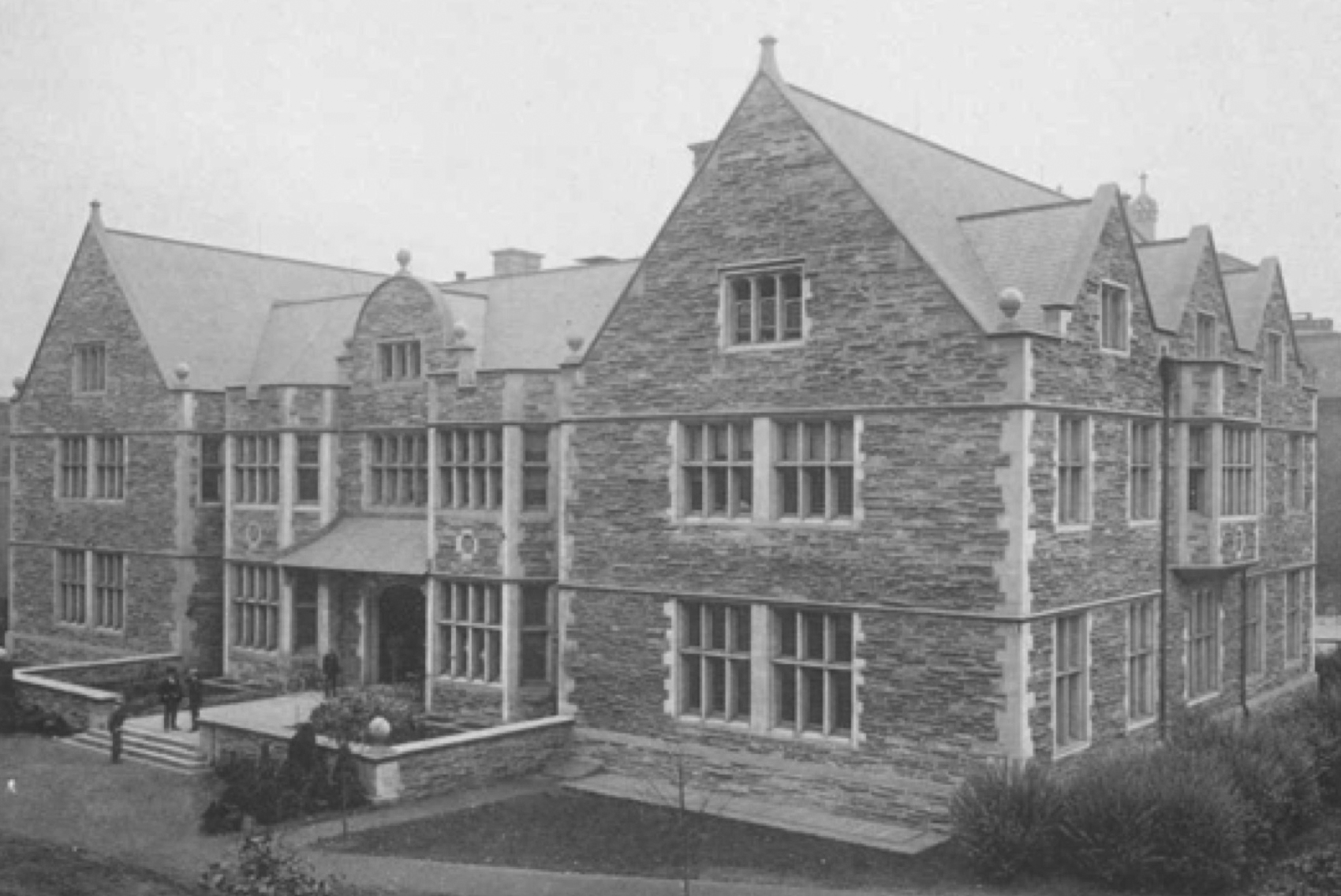

In contrast to the reformist intentions at Michigan, the espoused motivation for The Houston Club at the University of Pennsylvania, the nation’s first student union established in 1896, focused exclusively on instilling good manners and moral character. The brochure produced to celebrate the Houston Club’s opening included the following:

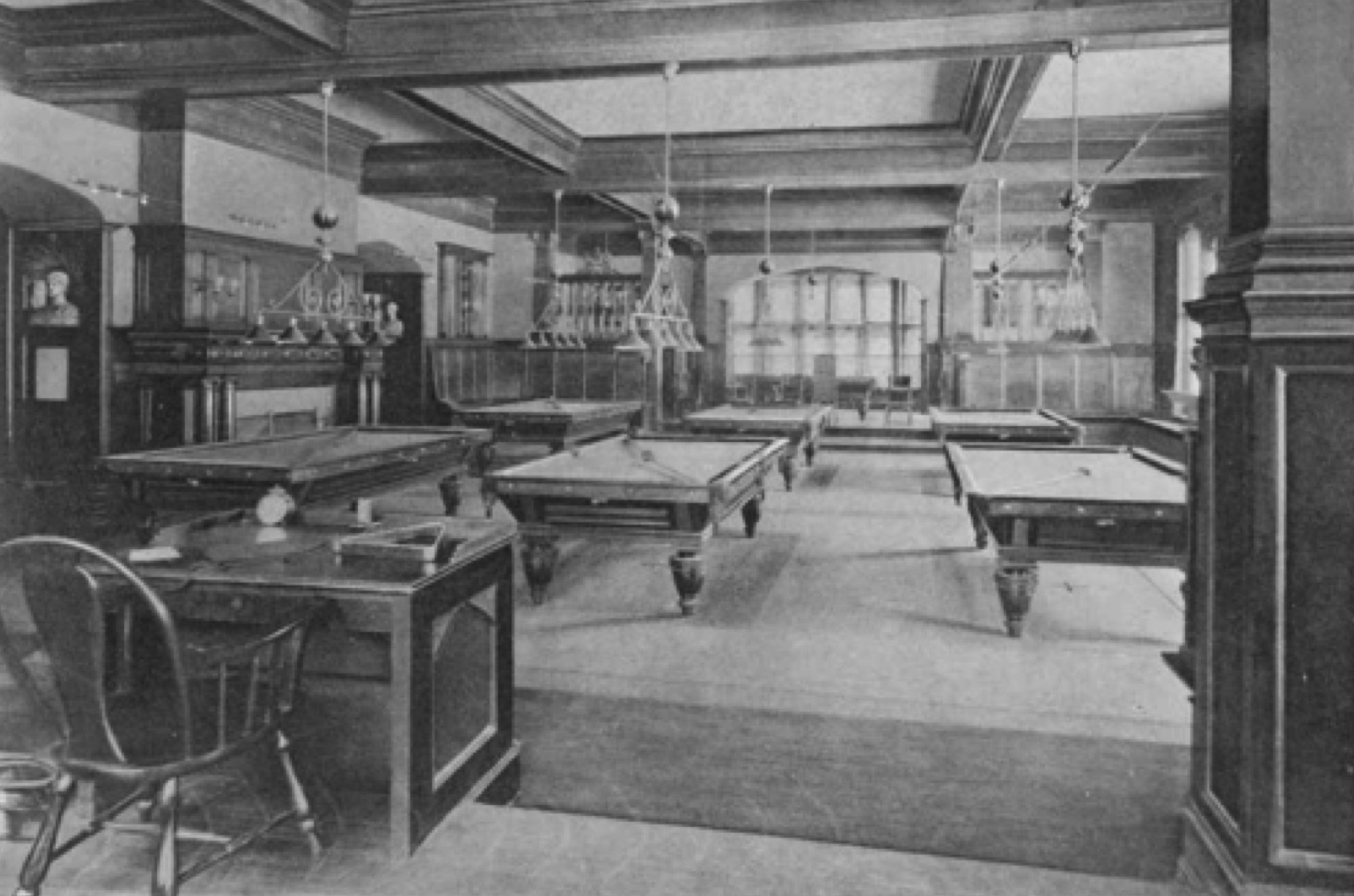

“There are nowhere softer rugs to tread, or more tasteful pictures to admire; no deeper, more comfortable leather chairs, better billiard and pool tables, truer bowling alleys, or more inviting baths and swimming pools. And yet all is as simple as it is graceful and convenient. The great, because silent and constant, influence of the Hall is not toward the breeding of luxury, but toward the cultivation of refinement and good manners. It is the recreation place of a community of gentlemen, and no young man who spends his odd moments here for four years will fail to carry away with him something of that excellent quiet dignity which is in its very atmosphere.”

Houston Hall, University of Pennsylvania. The nation’s first student union opened in 1896 (University of Pennsylvania Archives).

Billiard and Pool Room. Houston Hall, University of Pennsylvania. (University of Pennsylvania Archives).

Whereas the University of Pennsylvania’s union was thus celebrated for its refinement and opportunities for recreation, Bates’s list of required spaces for the Michigan Union was more concerned with enhancing the intellectual and social life of the campus.

It included:

“A large living room where students, the faculty and visiting alumni may meet at any time.

Rooms for college organizations, for the Alumni Association, for college publications, and Faculty club-rooms.

A large assembly room for meetings, college theatricals, lectures, concerts, etc.

A restaurant and cafe, the training table and banquet rooms.

A smoking room and reading room.

A library of the best recent history, biography, science, fiction, belle-lettres, etc.

Equipment for bowling, billiards, etc.

Bed rooms and a dormitory for distinguished guests and visiting alumni.”

The Progressive Architecture of the Michigan Union

While Bates and the University were establishing their vision of the role of the Michigan Union, Pond and Pond were developing, through their practice and writing, their design aesthetics and theories that would eventually provide the architectural expression for the building.

In his 1918 book, The Meaning of Architecture, Irving Pond provides evidence of the architects’ thinking as they designed the Michigan Union. First, Pond believed that the massing of a building is essential to how it is understood. Inveighing against the alienation of industrialized society and the emerging machine aesthetic of the International Style, Pond wrote:

“New materials and machinery have made it possible to fabricate units like laundry boxes on an immense scale, and to dispense them flat or on end in fantastic arrangement of broken meaningless masses.”

Firmly rooted in history, Pond countered that traditional forms carry emotional appeal. Pyramidal forms, including truncated ones like the Michigan Union tower, he believed are psychologically satisfying because they impart a sense of permanence and security. Citing the Michigan Union tower as a clear example of this principle at work, he states:

“I have produced this effect very simply and naturally by a process of elimination, rather than by buttressing walls where buttresses were unnecessary…. In brick structures the effect was gained by eliminating a half brick at the corners, then higher a whole brick and a half and so on.”

Looking up at the tower, one grasps the sense of structural integrity achieved by stepping back the tower walls and the careful articulation of its corners. The tower soars and lightens, yet firmly maintains its role as the anchor for the composition.

Michigan Union Tower. Photo by the author.

Stone window arches, where “right line flows into right line through curve.” Photo by author.

The Michigan Union tower gains expression by a pattern of eliminating bricks at its corners. In addition to the massing, the Ponds animate the building through the careful composition of the façade based on the structural resolution of vertical and horizontal forces. Writing in Architectural Record in 1905, Pond rebukes the increasingly popular Prairie School’s obsession with horizontality, which he faults as burdened with a “leaden sogginess.” Pond counters with a strategy for an orderly and evocative composition:

“Vertical forces in action, by the law of gravity, tend to work in right lines; horizontal forces acted upon by this same law tend to work in curves. Right line flows into right line through curve, and so no real architecture—and only structural architecture is real architecture—is perfect, from which either curve or right line excluded. The right line adds to the strength the sense of repose, the curve brings with it the joy of exhilaration….”

The squash blossom motif is seen throughout the building in various forms and configurations. Photo by author.

This principle is present throughout the façade of Michigan Union, including the stone arch mullions in the tower, and most notably in the rising sweep of curved mullions in the great, arched windows that bring light to the building’s social spaces. This structural expression imparts, what Pond called an “animating spirit,” and in so doing, communicates the Michigan Union’s mission of social uplift.

Concerning architectural ornamentation, Pond thought that it was best used to add visual interest when practicality limited the resolution of horizontal to vertical through curve:

“Misplaced ornament is as fatal to serenity and repose as an ill-timed jest.”

We can be assured that the Ponds were judicious in their use of ornamentation. So, what is one to make of the stylized squash blossom husk or calyx motif that is used throughout the building? The Ponds did not write specifically about this. It may be that, much in the same way that Egyptian builders used papyrus and Greek builders used acanthus to decorate their structures, these Midwestern architects chose the flower of a native plant species to better root the Michigan Union to its locale.

The Ponds’ approach to architectural expression was inseparable from the commitment they shared with Bates, Addams, and other reformers of the time, to the ideal of community. The architects further refined their aesthetic for collegiate student unions for subsequent commissions at Purdue University, Michigan State University, and the University of Kansas.

The Second Hundred Years

Nearly a century after its opening, U-M leaders and a team of architects (Workshop Architects of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, IDS of Troy, Michigan, and Harman Cox of Washington, DC) undertook a major renovation of the Michigan Union. The imperatives were to preserve the essential character of the building while creatively renewing its dynamic social programs. Hundreds of students participated in decision making through hands-on workshops and web-based surveys. A top priority for Michigan students was to establish an Idea Hub—a highly visible, flexible, and vibrant forum to support student organizations, and foster involvement, collaboration, creativity, and debate.

This renewal made abundantly clear that the values of social reform and community building—the roots of which were cultivated by Jane Addams at Hull House and given expression by the Ponds—still inspire the Michigan community. As it begins its second hundred years, commitment to these values ensures that the Michigan Union will remain indispensable to, and beloved by, future generations of Michigan students.